Hello! Welcome back to The Footprint, and happy Friday. Best of luck to everyone running the Chicago 13.1 this weekend.

📬 Edition #17 – featuring NFL veteran Justin Britt; Grand Slam Track director of athletes and racing Kyle Merber; and sustainability advocates Tina Muir and Natalia Trevino Amaro.

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here.

No End In Sight

(Courtesy of Justin Britt)

Justin Britt’s NFL career came to an abrupt end three years ago.

As a new season got underway in September 2022, he played a single game for the Houston Texans when everything “really rapidly spiraled into depression and anxiety, the same day,” he recalled in an interview. “Really quickly, I had to make a choice to protect myself.”

Britt stepped away, and tried to figure out what was happening. Six months later, the Texans released him.

“Football was kind of stolen from me,” Britt, 33, told The Footprint. I didn’t get a proper goodbye, didn’t get to step away the way I wanted to.”

It was his wife who suggested he head out on a run. He tried a mile, but couldn’t finish. “That really humbled me; angered me at the same time,” he said. On Strava, his first and second recorded runs were nine months apart.

He tried again. Running became a way of releasing pent-up energy from his body, and relieving pressure built up in his head. He challenged himself to go further, and faster, than he had thought possible.

Britt’s first half marathon last September “awoke something in me,” he said. Sunday’s Chicago 13.1 will be his sixth.

Life after the NFL “gets so quiet,” according to Britt, who says running helped him feel less alone. He has recommended it to other players moving on from football.

“Every run is another opportunity to figure yourself out,” he said. “It’s just given me a chance, outside my family, to feel like I have a purpose again, or something to strive for, on a daily basis.”

While NFL careers can be glamorous, high-profile and lucrative, Britt never felt this level of freedom. “So much of my life was controlled,” he explained. With running, “if I wanna go fast, I can go fast; if I wanna go slow, I can go slow; If I wanna walk, I can stop and I can walk.”

But there are some similarities with his former life.

“I like showing up to race day,” said Britt. “We all put in the miles, hopefully. We all show up. You can feel the anxiety, the excitement, the unknown feeling of how it’s going to go – you can feel that from everybody.

“From setting out your uniform the night before to showing up and getting in your corral and freezing your butt off on race day, it just – all of it – reminds me so much, and gives me the same feeling mentally, of playing in the NFL.”

In this new chapter, however, Britt is pushing himself in different ways – chasing goals without the weight of expectations, spurred by hope, not fear. “I don’t think I’ll be a pro runner. But we’ll have some fun doing it.”

This won’t be his last trip to Chicago. In October, he’ll return to run his first marathon. Training starts next month.

There was a time Britt insisted he never would run a full marathon. “I saw the way people were walking away from them,” he said. But tackling the half – going further, and getting faster, on his own terms – made him wonder. What next?

“Football comes to an end. And you know it’s going to come to an end,” he noted. “But God willing, running you can do ‘til you die. We’re not going to be done anytime soon.”

Building A Hype Machine

Kyle Merber and Michael Johnson (Courtesy of Grand Slam Track)

Michael Johnson, by his own admission, is not a patient man. Straight out the blocks, the four-time Olympic champion sprinter hailed his new venture as a turning point for track.

Grand Slam Track is “revolutionizing the track landscape,” he declared last summer, “allowing our sport to remain at the forefront of the sporting world year round, and pushing our superstar racers to break new ground in their personal storytelling, competitive success, and marketability.”

At the time, the start-up had only announced one racer. But it was an unambiguous statement of intent.

Over the past two months, fans and operators from across the athletics world have been able to see for themselves if the fundamental premise behind Grand Slam Track – the world’s fastest men and women, each racing twice over three days – lived up to the hype.

Rome wasn’t built in a day. Revolutions start small. And highly ambitious sports franchises, however big their budgets, don’t start out as top-flight leagues.

“We put the pressure on ourselves to come out swinging. We decided we were going to start with the Super Bowl,” Kyle Merber, director of athletes and racing at Grand Slam Track, told The Footprint. “At the end of the day, we are a start-up. And we’re learning along the way. We’re nimble and we’re figuring things out.”

The first meet in Kingston showed promise, but underlined how far Grand Slam Track will need to go to realize its lofty dream. Some of the best athletes in the world took part in compelling races before largely empty stands at Jamaica’s National Stadium.

Momentum took hold at the second meet in Miami. Rivalries emerged. Redemption was sought. The atmosphere was livelier, with a reportedly sold-out crowd largely filling an admittedly smaller venue.

(Courtesy of Grand Slam Track)

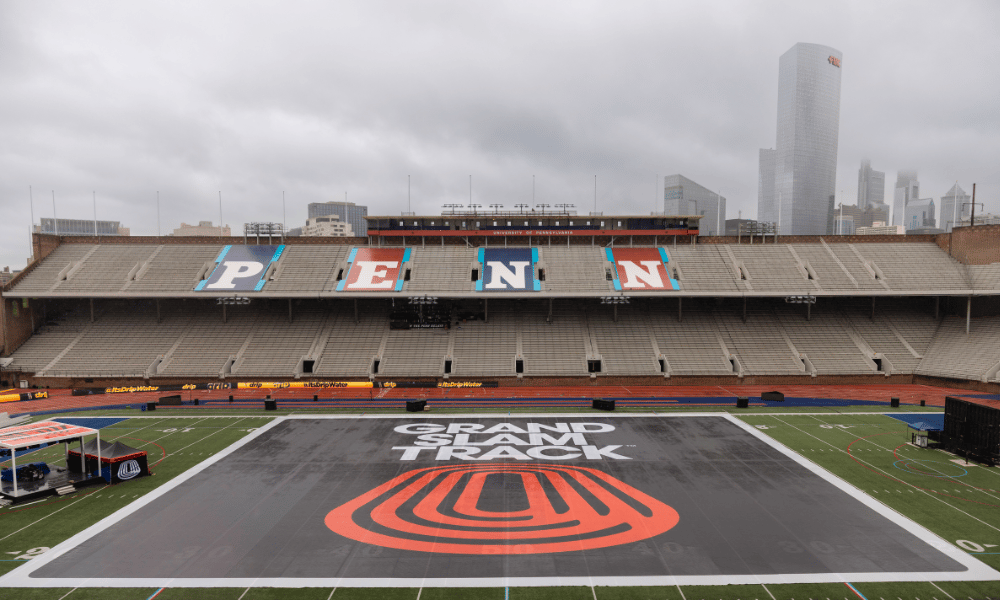

This weekend Grand Slam Track arrives in Philadelphia, and by far its biggest stadium yet, for its third meet. For a league designed to make track mainstream, one question will echo around Franklin Field: is this working?

“The big takeaway I have, coming out of Kingston and Miami, is just the concept works,” said Merber. The core format of Grand Slam Track takes athletes out of their comfort zone, and beyond their main event, to compete in an additional race.

In the short distance field, for example, Cole Hocker, Josh Kerr and Yared Nuguse – gold, silver and bronze medalists in the 1500m at the Paris 2024 Olympics, respectively – are required to also race the 800m, against the likes of Marco Arop, Olympic silver medalist at this distance.

“It elevates the product,” said Merber, “and it creates new narratives and extra storylines and match-ups that we would never otherwise see.”

The challenge is both lining up such action for fans to see, and making sure they actually watch. Millions watch Olympic athletics events once every four years; Grand Slam Track is designed to catch their attention in between.

Up to 250,000 US TV viewers tuned into the first two meets on the CW: respectable for a new league, but a long way from the audience it wants to attract.

The Philadelphia meet has been condensed from three days into two, squeezing races closer together, “following consultations with and feedback from competitors, coaches, and fans,” according to organizers. “We’ve said all along we want to listen,” said Johnson.

It is, as Merber acknowledged, still figuring things out.

The goal, he said, is to win over the sport’s biggest fans first, in the hope this generates an unignorable buzz – pointing to the football match, or basketball game, that draws in curious viewers who can’t help but notice the noise.

“There’s so much hype and excitement around, and so much fandom, you’re suddenly wrapped up in the exposure to it,” said Merber. “That’s what we need to do with track.”

AROUND AND ABOUT

📱 Put your phone away. Some runners are filming every mile of their race. That’s not just annoying — it’s dangerous, Ashley Mateo argues in Runners World

💥 Running’s third great boom. A digitally native generation is making the sport fashionable, communal and more diverse than ever, Sean Ingle writes in the Guardian

🏃 The runway of influencers. As more brands turn to prominent social media figures to help sell their products, Allison Lynch asks how long they can last

🏅 Coming to a stadium near you. Women’s-only track meet Athlos will expand into a track and field league with multiple meets from 2026, Chris Chavez reports for Citius Mag

🎧 Running doesn’t have to suck. Performance coach and author Steve Magness talked to The Trailhead podcast about zooming out and finding perspective (Apple | Spotify | Pocket Casts)

Ripples and Waves

Tina Muir and Natalia Trevino Amaro (Courtesy of New York Road Runners)

On the eve of this month’s Brooklyn Half Marathon, as thousands picked up their bibs, a handful of runners gathered nearby.

They each took a pair of gloves and a trash bag, and set out on a light run. The pre-race plog – a combination of the Swedish terms plocka upp (pick up) and jogga (jog) – had begun.

“Imagine if every runner picked up one or two pieces of trash a day. That really would make a big impact,” said Tina Muir, a climate action advocate and former pro runner for Great Britain. “But beyond that, it’s also about the ripples and the waves that it sends. People that are out walking, or might be driving past: they see you doing this thing. They know that you are actively choosing to give back.

“You are actively choosing to do something that makes our world a better place. And for many people, it then inspires them to do something good in their own lives.”

By her side was sustainable fashion designer Natalia Trevino Amaro, who made a skirt from old gel wrappers, protein bar wrappers and bottles that Muir used for the 2023 New York City Marathon.

“So many aspects of running can be done sustainably. There’s a lot of waste in it,” said Trevino Amaro. “So it’s just kind of a statement piece on all the waste created.”

Muir has been working with big race organizers, like New York Road Runners and Chicago Event Management, vying to reduce the environmental impact of their events (tomorrow at 8.30am in Garfield Park, she’s leading a plog ahead of the Chicago 13.1) and founded Racing for Sustainability, a non-profit, to help smaller races do the same.

But she wants runners to step up, too.

“One of the things I feel most strongly, most passionately, about is runners carrying their own hydration and fuel,” said Muir. She wants more people to hold water and use reusable gel flasks, rather than rely on races to provide cups, bottles and packets.

“I really genuinely believe that upwards of 60% of runners could carry their own water,” she added, “and that’s the kind of pipe dream that I would love to see happen: runners taking accountability for their own fuel and hydration.”

Trevino Amaro started running herself last year. Brooklyn, which she ran with Muir, in matching upcycled skirts, was her first half. It was a reminder, for her, of the power of working with others.

“I could’ve for sure done it alone, but I know I would’ve had a harder time with it,” said Trevino Amaro. “I think that sentiment transcends to everything – even the climate movement.”

RECENT EDITIONS

#16 What Running Should Be | former pro Serena Burla returns to racing

#15 Dreaming Bigger | Faith Kipyegon’s bid to break four minutes in the mile

#14 Space On The Mountaintop | industry leader Frankie Ruiz on sustaining the running boom

Thanks for reading! Let me know what you think: just hit ‘reply,’ or email me.

Have a great weekend.

– Callum